I hadn’t expected that the second chapter of Anything is Possible would not be about Tommy, an elderly man we’d met prior. Instead, we’re introduced to a new character, a character to whom I found myself expressing sympathy. If I am honest, though, at first I had much different opinion of Patty. I thought as though she was judgmental, especially towards the Barton’s. In the very beginning, she mentions, when they were younger, that Lucy Barton’s house was tiny, and that it smelled. It wasn’t until later, perhaps somewhere in the middle of the chapter, that I felt sympathy for her. Patty describes in detail having witnessed her mother cheat on her father. After having read that, I knew immediately why Patty acted the way she did towards her mother. Throughout the chapter, it becomes painfully clear that the people of the town, adolescent and adult, treat Patty with very little respect.

I hadn’t expected that the second chapter of Anything is Possible would not be about Tommy, an elderly man we’d met prior. Instead, we’re introduced to a new character, a character to whom I found myself expressing sympathy. If I am honest, though, at first I had much different opinion of Patty. I thought as though she was judgmental, especially towards the Barton’s. In the very beginning, she mentions, when they were younger, that Lucy Barton’s house was tiny, and that it smelled. It wasn’t until later, perhaps somewhere in the middle of the chapter, that I felt sympathy for her. Patty describes in detail having witnessed her mother cheat on her father. After having read that, I knew immediately why Patty acted the way she did towards her mother. Throughout the chapter, it becomes painfully clear that the people of the town, adolescent and adult, treat Patty with very little respect.

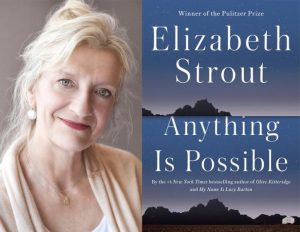

Again, I can say I found Strout’s writing wonderful, and clean. There was seldom a moment in which I wasn’t completely, and utterly engaged with the text. I loved that Strout explained the shame Patty feels towards her own body, after having seen her mother unclothed. Strout writes:

“Her mother was crying, gasping, shrieking, and there was the sound of skin being slapped, and Patty had run upstairs and seen her mother astride Mr. Delaney–Patty’s Spanish teacher!–and her mother’s breasts were swaying and this man was spanking her mother and his mouth reached up and took her mother’s breast and her mother wailed. And what Patty never forgot was the look of her mother’s eyes, they were wild; her mother could not stop herself from wailing, this is what Patty saw, her mother’s breasts and her mother’s eyes looking at her–yet unable to stop what was coming from her mouth.” (51)

Strout describes in prepossessing detail this crude and offensive sexual act. The language she uses is quotidian, and yet beautiful, nonetheless.